Japan school lunch program is more than just a meal—it’s a cornerstone of education, nutrition, and cultural identity. Since its humble beginnings in 1889, the program has transformed dramatically, reflecting Japan’s social, economic, and cultural shifts through the twentieth century. From post-war bread and powdered milk to today’s rice-based menus with global influences, the story of Japan’s school lunches is a delicious journey of resilience and innovation. Let’s explore how these meals have nourished generations and shaped a nation.

The Birth of a Movement: Japan’s First School Lunch

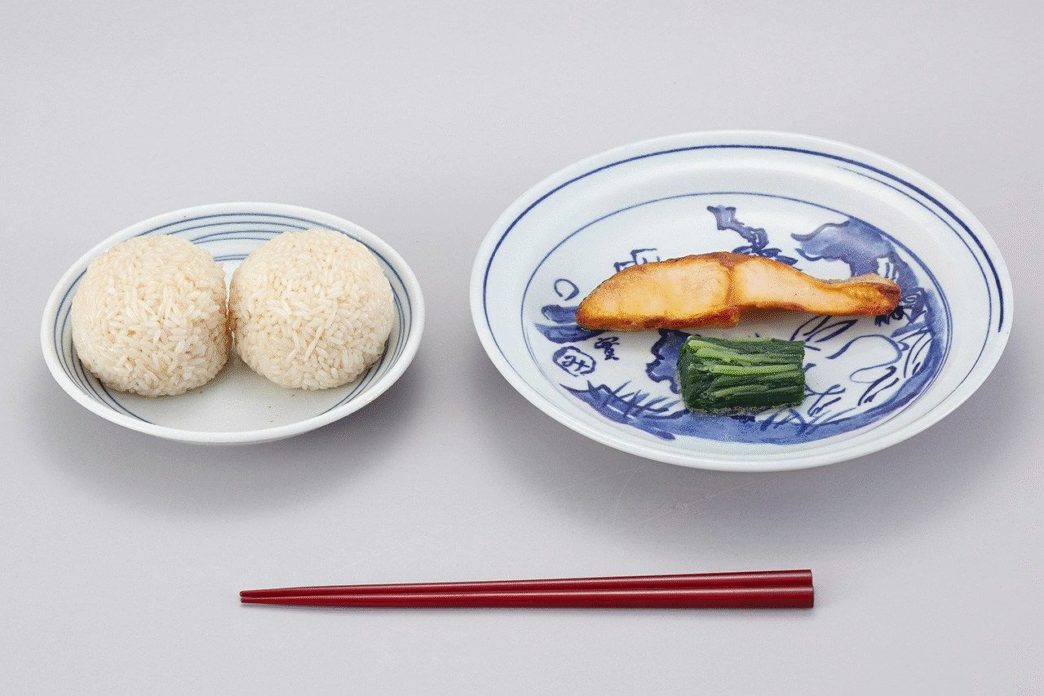

The seeds of Japan’s school lunch program were sown in 1889 at Daitokuji temple in Tsuruoka, Yamagata Prefecture. Here, compassionate priests served free lunches of salted rice balls, salted salmon, and pickled greens to impoverished children, funded by alms. This initiative, born in the rice-rich Shōnai region, set a precedent: provide nutritious meals without stigmatizing those in need. A monument in Tsuruoka still honors this pioneering effort, which embodied a spirit of community and mutual aid.

As similar programs emerged across Japan, often funded by local governments or wealthy donors, school lunches gained traction. Natural disasters like the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake and famines in the 1930s spurred further expansion, with the government formalizing policies in the 1930s to feed hungry children. During Japan’s militaristic era, lunches were also seen as a tool to boost children’s health for national strength. However, wartime shortages halted most programs by World War II’s end, leaving many children malnourished—80% of Tokyo’s children in a postwar survey ate one meal or less daily.

Post-War Revival: Bread, Milk, and International Aid

The end of World War II in 1945 marked a turning point. Japan’s food crisis alarmed the Allied occupation forces, who feared social unrest. In 1946, at the urging of former U.S. President Herbert Hoover, school lunches restarted with U.S. support. On Christmas Eve, 250,000 children in Tokyo, Kanagawa, and Chiba received tomato stew and powdered skim milk, courtesy of the Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia (LARA). By 1950, the U.S. Government and Relief in Occupied Areas (GARIOA) fund enabled full meals—bread, milk, and side dishes—for 1.3 million urban schoolchildren twice weekly.

When Japan regained sovereignty in 1951, GARIOA funding ceased, shifting costs to families. A national campaign pushed for government subsidies, and by 1952, flour subsidies revived the program. The 1954 School Lunch Program Act cemented lunches as an educational pillar, with goals to teach nutrition, foster social skills, promote healthy habits, and deepen understanding of food systems. This act set Japan’s program apart globally, blending nutrition with learning.

Iconic Foods and Their Stories

Japan’s school lunches evolved with the times, introducing foods that became nostalgic touchstones for generations. Here are some highlights:

- Deep-Fried Whale (1950s–1980s): A protein-packed staple in the 1950s, whale meat was cheap (one-third the price of pork) and abundant due to Japan’s whaling industry. Older Japanese fondly recall it as a school lunch regular until it faded from menus by 1980.

- Agepan (1952–Present): Invented in 1952 by a Tokyo school cook, these sugar-and-kinako-coated fried bread rolls were a sweet solution to keep bread fresh for sick children. A nationwide hit by the 1960s, agepan remains a beloved snack in stores today.

- Milk (1940s–1960s): Post-war lunches featured powdered skim milk, which was nutritious but unpopular due to its odor and texture. By the mid-1960s, fresh milk replaced it, becoming a staple in iconic glass bottles.

- Soft Noodles (1960s–1980s): Known as sofuto men, these pre-packaged noodles, served with curry or meat sauce, were a 1960 innovation to prevent sogginess. They waned as udon and Chinese noodles took over.

- Rice (1976–Present): Surprisingly, rice wasn’t a standard until 1976. Post-war rice shortages and Westernized diets delayed its adoption. Surpluses in the 1960s, coupled with 1979 subsidies, made rice a mainstay, often cooked off-site in bread factories.

A Shift to Rice and Cultural Fusion: Japan School Lunch

The introduction of rice in 1976 marked a cultural homecoming. While bread dominated post-war menus due to rice shortages, improved agricultural technology and economic growth led to rice surpluses by the 1960s. The government, keen to reduce reliance on imported wheat, embraced rice as a school lunch staple. By the 1980s, rice was paired with diverse side dishes, blending Japanese traditions with Western influences—a nod to the growing popularity of family restaurants and global cuisines.

In 1983, the Ministry of Agriculture promoted a “Japanese-style diet” that married rice with international flavors, preserving cultural roots while embracing diversity. The 2005 Food and Nutrition Education Act and 2008 amendments to the School Lunch Program Act reinforced this balance, emphasizing food education (shokuiku) to teach children about nutrition, sustainability, and cultural heritage.

The Legacy of Japan’s School Lunches

Today, Japan’s school lunches are a global model, known for their nutrition, affordability, and educational value. They’ve come a long way from the simple rice balls of 1889, adapting to crises, cultural shifts, and global influences. The program’s success lies in its dual focus: feeding bodies and minds. Students learn about healthy eating, etiquette, and food production while enjoying balanced meals that reflect Japan’s evolving identity.

From whale meat to agepan, powdered milk to rice, each era’s menu tells a story of resilience and ingenuity. As Japan continues to innovate, its school lunches remain a testament to the power of food to unite, educate, and nourish a nation.

Also Read: Celebrate Japanese Culture at the Japan Parade in NYC!

For more, visit Nippon.com. Originally published in Japanese on January 24, 2025. Images courtesy of Japan Sport Council.

Note: Some historical details, like the exact scope of early programs, may vary by source, but this article draws on Nippon.com and Ministry of Education data for accuracy.

Source: https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/g02481/